On Saturday I attended a meeting in Canberra of the anti-Islam Q Society. The event [PDF], called “Understanding Islam and how it will Impact on Australian Communities,” featured speeches by prominent Sydney anti-burqa artist Sergio Redegalli and UK anti-mosque lawyer Gavin Boby of the Law and Freedom Foundation.

After last week emailing the ACT chapter an expression of interest in attending, I was informed that the meeting’s location wouldn’t be revealed until two days beforehand to “reduce the likelihood of the venue details being broadcast on Twitter or Facebook, and someone uninvited making a nuisance of themselves.” Upon arrival, I identified myself to the door staff and bouncer as a freelance journalist (sounds a bit cooler than “internet blóger”) and was refused entry because the public event was closed to the media. However, the meeting’s organiser, Debbie Robinson, intervened and overturned that decision after making a phone call to an unidentified person. Before giving me a wristband and letting me through, the lady in charge of the door told me sternly that Q Society had been unfairly represented and “kicked” by the media, and that I needed to understand why they were wary about me.

Inside the hired conference room was a crowd of around 30 people, with the average age somewhere around 50-years-old. The attendees appeared to be from a range of backgrounds; indeed, over the next two-and-a-half hours I would discover that some of them were Iraqi-Australian and Pakistani-Australian Christians. As I listened to Redegally and Boby’s speeches, I learned that several hundred Muslims were clashing with police on the streets of Sydney, in protest against a YouTube video based on the kinds of ideas espoused by the Q Society.

As I reflected afterwards on the two separate yet related events, I couldn’t help but draw comparisons between the Q Society and the Muslims demonstrating in Hyde Park — both groups of people were expressing their opinions as is their right in Australia, both were driven by an intolerant frustration and perhaps even hate, and both are at the fringes of this country’s political and social spectrum. It was interesting to see so much similarity in the methods and motivations of two quite opposite yet equally extreme movements that promote ideas many Australians would find offensive.

In the grand scheme, there weren’t actually that many more people protesting in Sydney’s CBD than there were in that beige meeting room in Canberra, and even if there had been no violence I would’ve felt safe placing a bet on which event would make the newspapers the next day. But there was violence, and those protesters in Sydney have been rightly condemned for that violence, both actual and suggested.

In attempting to understand Saturday’s street protest it serves no useful purpose to generalise about all Muslims due to the actions of a few, although that’s exactly what we are seeing in some sections of the community and commentariat. And those generalisations don’t even stand up to basic scrutiny. Take a look, for instance, at photos of Saturday’s violence and you’ll see over and over again protesters carrying a black flag with white Arabic lettering.

This is the flag of Hizb ut-Tahrir, a global Sunni Islamic movement with the goal of uniting the world’s Muslims under a single caliphate. The organisation has a controversial presence in Australia and has attracted calls for it to be listed as a terrorist organisation. The prominence of Hizb ut-Tahrir’s flag in pictures from the weekend suggests that its numbers were strong in the crowd.

Members of Hizb ut-Tahrir certainly are Muslims, but they are just a small, fringe sub-section of the wider Islamic community. Even the Daily Telegraph has acknowledged that “Hizb ut-Tahrir does not represent most Muslims in Australia.” Those who rioted on Saturday are no more representative of most Muslims than the Cronulla rioters of 2005 are of most Australians, though both events shame us all.

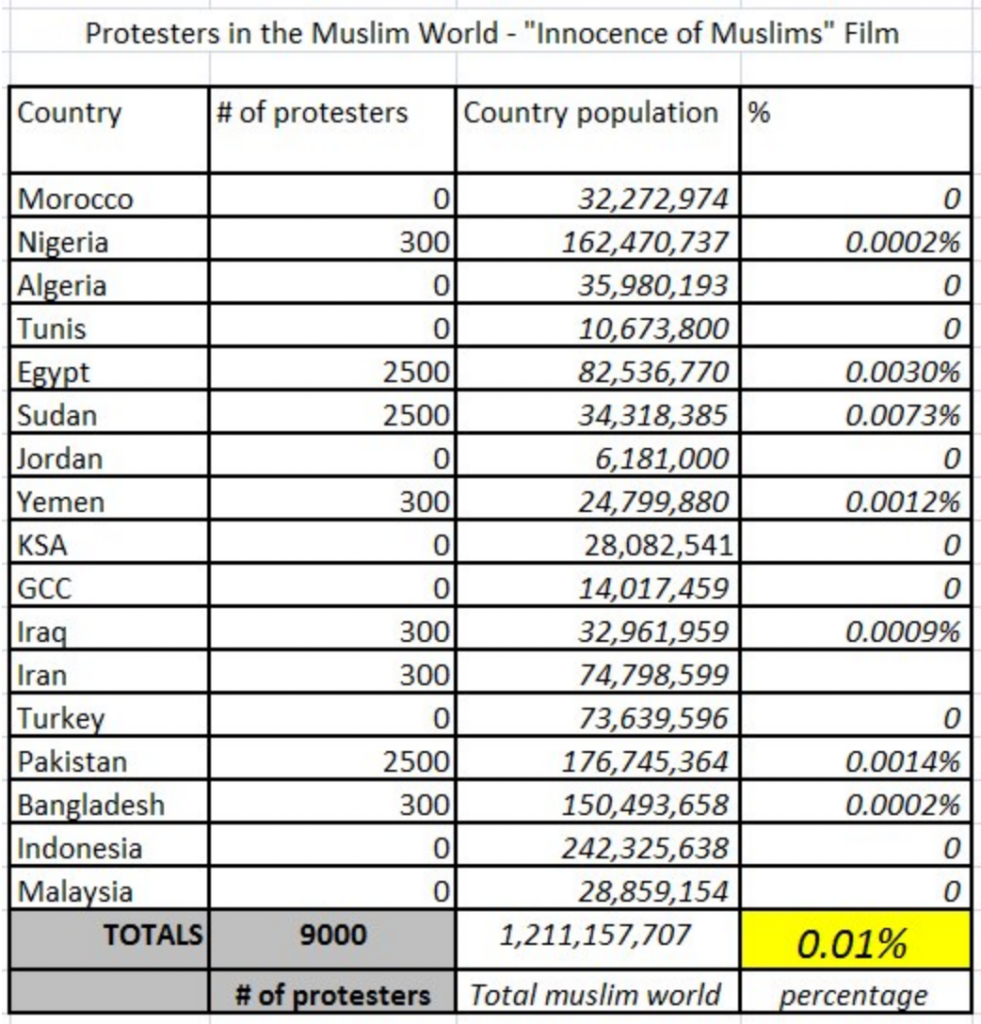

Worldwide, the trend is similar. Muslims protesting against the YouTube video around the world this past week, according to Susan Carland’s maths, make up a massive 0.01% of the total populations of majority Muslim countries.

And even if we take the upper figure of 500 protesters out in the Sydney CBD on the weekend, that represents 0.001% of the 476,300 identified as Muslims by the ABS in 2011. Hardly a groundswell of violence here or overseas.

At the Q Society meeting I heard endless generalisations about Muslims: they “seek out violent religion”, produce only an “increased crime rates”, are “dependent on welfare flows”, and their mosques give nothing to communities except “an abundant supply of shoes.” Despite the organisation’s stated mission to spread information about Islam, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that members are motivated by something other than a simple commitment to truth. Often cited as a source by speakers was the website Jihad Watch.

In the same vein, it serves no purpose to generalise about all non-Muslim Australians due to the view expressed by the Q Society and @boltcomments. These people represent a small but vocal minority.

Something that Muslim protesters around the world and the Q Society membership shares is intolerance. Those Muslims rallying violently against a frankly laughable YouTube video are clearly incapable or unwilling to tolerate the kind of satirical content that most people can brush off without burning a flag, even if that content is malicious and offensive. Q Society members are upfront about their feelings about Muslims; as Gavin Boby said at the meeting, “It’s good to be among so many Islamophobes.” In both cases, it is often intolerance in part born of insecurity and fear.

In the wake of a week of protest across the Middle East, Fouad Ajami wrote an interesting piece in the Washington Post, asking why it is that the Arab world is so easily offended:

Even as Arabs insist that their defects were inflicted on them by outsiders, they know their weaknesses. Younger Arabs today can be brittle and proud about their culture, yet deeply ashamed of what they see around them. They know that more than 300 million Arabs have fallen to economic stagnation and cultural decline. They know that the standing of Arab states along the measures that matter — political freedom, status of women, economic growth — is low. In the privacy of their own language, in daily chatter on the street, on blogs and in the media, and in works of art and fiction, they probe endlessly what befell them.

Q Society members, on the other hand, are threatened by changes they see or imagine taking place in their communities, and feel disenfranchised from the political processes governing these changes. They fear Islam for its perceived threat to their “way of life”, which would be unacceptably altered if Islam was thrown into the mix of their local communities. They know that their views often attract labels such as “racist” and “bigot” which further adds to feelings of marginalisation.

Many of the fears expressed at the Q Society meeting were based on creative extrapolation, anecdotes posing as data, and plain falsehoods. Gavin Boby claimed that property values in an area will drop 10-15% as soon as a mosque application is lodged; Sergio Redegalli spoke of how a burqa could impair a driver’s vision and cause an accident, or how a man wearing a burqa could enter a female toilet and … he left space for others to fill in the blank; discussion during the meeting’s Q&A session turned at one point to systematic gang rape and pimping by Muslim men; Boby at one point noted ominously that everything looked fine in 1930s Germany but we all know what happened next.

When people are afraid and insecure they close ranks and prepare to fight back, even if, as Waleed Aly wrote today, they don’t even really know what it is they’re fighting back against:

This is the behaviour of a drunkenly humiliated people: swinging wildly with the hope of landing a blow, any blow, somewhere, anywhere. There’s nothing strategic or calculated about this … It feels good. It feels powerful. This is why people yell pointlessly or punch walls when frustrated. It’s not instrumental. It doesn’t achieve anything directly. But it is catharsis.

What Australia saw on Saturday in Sydney, and I saw in Canberra, are two good examples. The Muslims in Sydney chose to fight back against a grab-bag of amorphous grievances with public demonstration and violence, while the Q Society approaches its fight in a very different way.

Over the course of the meeting, many metaphors emerged to describe the war being waged with Islam: mosques as “beachheads” and “command and control centres,” efforts to “slow the tide, stop the tide, and then reverse the tide,” the need to gather “intel,” and the grand statement that “civilisation’s first duty is to survive.” Gavin Boby outlined the four stages of Islamic expansion into neighbourhoods (“Parking Jihad”; “Domination”; “Sinister”; and “Intimidation”) and the process by which his organisation coordinates objections to mosque planning applications in defence of ordinary, decent, “salt of the earth” people.

The spread and expansion of Islamic populations across the world was painted as a deliberate attempt to conquer, and the hijab nothing more than a political statement. Birth rates by religion were compared and it was claimed that each non-Muslim woman would need to have seven children for the West to keep pace with Islam, including infertile and gay women, and those who “don’t like sex”. Redegalli outlined his plans to create a new artwork called the “Muhammed Sutra” featuring “the Paedophile Muhammed”. Boby encouraged the Society’s member to continue their fight because it’s “fun to win” over the “beardy-weirdy guys in caps and maternity dresses.”

It was a strange afternoon. I watched on Twitter as a violent and hateful protest took place in Sydney, triggered by ideas and opinions I find distasteful, while sitting in a room listening to people talk about ideas and opinions I find equally distasteful. I found the arguments put forward at the Q Society meeting lacking logic, sometimes offensive, and somewhat at odds with the its pledge to “never resort to … the use of lies, profanity and insults.” Hate is a strong word and it’s a tricky thing to identify at times, but I’m not entirely sure what I witnessed wasn’t driven at least in part by hate. Marks for doing it without violence, though.

Photo by marfis75